Why Train with Your Menstrual Cycle?

Understanding your body is critical to maximizing your potential as a femal athlete. Garmin and Wild.AI, a 2022 Garmin Health Award Winner in Engagement, can help.

Understanding your body is critical to maximising your potential as a female athlete — and this includes understanding your menstrual cycle.

The goal of Garmin Connect is to help you see and understand your health data — including sleep, stress, menstrual cycle (if logged) and much more*. The menstrual cycle tracking feature in Garmin Connect will provide information throughout certain parts of your cycle, but if you’re looking for more training guidance with Garmin data, integrating with Wild.AI may be a good fit for you. The integration will pull over the relevant Garmin health data into Wild.AI for even better guidance. Still not sure about tracking or learning how to train with your cycle? Keep reading to learn more.

How does my cycle affect my performance?

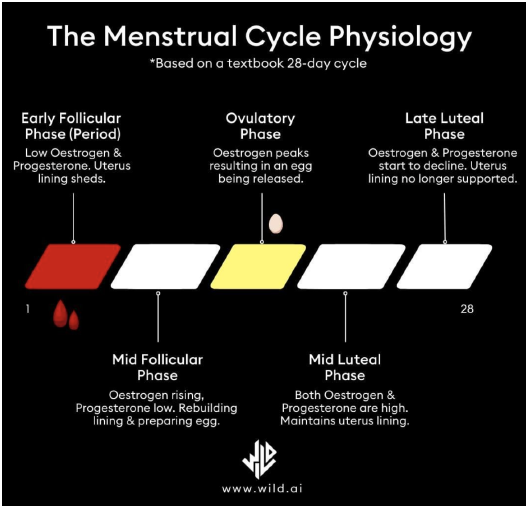

Your hormones fluctuate throughout your menstrual cycle — and that affects your muscles, bones and energy metabolism. The chart below outlines the physiologic impact estrogen and progesterone have on the body. Estrogen is typically higher in the first part of your cycle, while progesterone is present in the second half.

| ESTROGEN | – Increase in muscular strength1 – Increase in fat utilisation and a decrease in carbohydrate and protein breakdown3 – May improve endurance performance4 – Increase in neural drive to muscles2 – Increase in fluid retention1 – Protection against muscle damage because of increased antioxidant ability2 – May increase sensitivity to serotonin (negative effect of estrogen)10 |

| PROGESTERONE | – Increase in protein breakdown1 – Decrease in gut permeability1 – Anti-estrogenic effects (i.e., opposite everything estrogen does)1 |

What are the benefits of tracking your menstrual cycle and its related symptoms?

Menstrual cycle tracking may seem unnecessary given that your period is often accompanied by bleeding. But having a regularly recurring period is a sign of good health. Minimising the menstrual cycle to solely your period eliminates several other phases of your monthly cycle where you may feel different. Additionally, not everyone experiences an average 28-day menstrual cycle, and tracking your symptoms across different phases can help you understand your individual patterns.

Tracking can also help predict symptom onset and severity, help “periodise” your training programmes, mitigate any negative symptoms and help you adapt to days you may be more ready to perform maximally. Additionally, deviation from what you would consider your normal cycle could be a sign of something deeper and that it might be time to visit your primary care physician.

Trends in your monthly cycle can help you uncover your individual patterns to help you better understand how to train, fuel and recover as a woman. Endurance training plans available in Wild.AI are automatically adapted to your menstrual cycle phases. You’ll receive pre- and post-training nutrition and recovery recommendations based on cycle phases as well as how to mitigate common menstrual symptoms.

Should I be exercising/eating according to my hormone levels?

Learning your individual cycle-related symptoms through tracking can help you understand how exercising and fueling may need to be adapted based on individual phases. In this way, you’ll be able to tune into what’s happening in your cycle and adjust based on how you feel in that phase or on that day. The good news is that the actual adjustments you need to make can be supported through what we know about the impact of female sex hormones on female physiology and metabolism.

Tracking through Wild.AI can provide daily insights on your physiology and readiness to perform. This overview can take you more in depth into your physiology:

Early Follicular Phase (aka the period): The menstrual cycle “begins” with the early follicular phase. During this time, the uterine wall begins to shed its inner lining — more commonly called a period.

The inflammatory response that begins during pre-menstruation continues into the early follicular phase as you begin your period. During this phase, blood vessels near the uterus constrict and the uterine muscle contracts, often leading to cramping5. While programming around your period should be based entirely on personal comfort, exercising during this phase has been shown to mediate symptoms6. The lower hormone profile in this phase encourages more reliance on carbohydrates, which may enhance performance in higher intensity exercises, such as anaerobic intervals or sprinting7.

Mid Follicular Phase: The follicular phase is focused on developing the follicle and thickening the uterine lining11.

This phase is marked by rising estrogen levels. Estrogen promotes increased carbohydrate sensitivity upon muscular contraction that may support high-intensity aerobic activity4. When combined with increased neural drive (i.e., your brain’s ability to activate muscles) and a potential increase in muscular strength encouraged by estrogen, the follicular phase may be a good time to focus on strength training8,9. What’s more, this phase is reported to have enhanced recovery, which may be beneficial for intense lifting sessions9.

Ovulatory Phase: Ovulation occurs around the midpoint of your cycle. During ovulation, the mature egg is released and travels through the fallopian tube. Ovulation is marked by a luteinizing hormone (LH) surge that is encouraged through extremely high levels of estrogen11.

Ovulation is stimulated, ultimately, by continually increasing levels of estrogen. Because of estrogen’s anabolic effect, this is a good time to focus on strength training1.

Mid Luteal Phase: The mid-luteal phase is focused on preparing the uterus for implantation of a fertilised egg. During this time, progesterone helps prepare the corpus luteum and endometrium11.

During the mid-luteal phase, progesterone reaches its peak, and estrogen begins to rise again. Estrogen’s encouragement of a fat metabolism, coupled with lower carbohydrate metabolism due to progesterone may require a higher carbohydrate intake around training. This may also suggest that the luteal phase is better suited for longer endurance activities4. However, both estrogen and progesterone discourage the production of glucose in the liver, requiring sugar supplements to be taken during longer endurance activities (beyond 90 minutes)4.

Also, during the luteal phase, progesterone encourages protein breakdown post-training, suggesting that it may also be beneficial to focus on protein timing and intake during this phase4.

Late Luteal Phase: If no embryo is implanted in the endometrium, the corpus luteum degenerates, estrogen and progesterone regress to early follicular levels, and the body prepares to shed the uterine lining.

The premenstrual, or late luteal phase, is often accompanied by a variety of symptoms that are more commonly referred to as PMS (premenstrual syndrome). During this phase, there is an increase in inflammation that occurs in preparation for your period. When coupled with intense exercise, this time may require adjustments in diet and micronutrients that can help combat fatigue and pain-related symptoms1.

Perimenopause and Menopause:

Due to the fluctuations in estrogen that occur during perimenopause, and the resulting low levels that are present during menopause, it is highly suggested that exercise during this phase of life include some sort of loading (i.e., resistance training) to minimise bone density loss. Performing exercises that load the spine, like squatting, is most important, because that is the area that is most susceptible to osteoporosis and subsequent fractures. This in combination with a high protein intake can combat undesirable changes in body composition and bone loss.

Ready to get in tune with your body? You can purchase a smartwatch that’s compatible with Garmin women’s health tracking here. You can download the Wild.AI app here.

*Find information on metric accuracy here.

References

1 Bruinvels, Georgie, et al. “Menstrual Cycle: The Importance of Both the Phases and the Transitions Between Phases on Training and Performance.” Sports Medicine, vol. 52, no. 7, July 2022, pp. 1457–60, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01691-2.

2 McNulty, Kelly Lee, et al. “The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Sports Medicine, vol. 50, no. 10, Oct. 2020, pp. 1813–27, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01319-3.

3 Helm, Macy M., et al. “Impact of Nutrition-Based Interventions on Athletic Performance during Menstrual Cycle Phases: A Review.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 18, no. 12, June 2021, p. 6294, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126294.

4 Oosthuyse, Tanja, and Andrew N. Bosch. “The Effect of the Menstrual Cycle on Exercise Metabolism: Implications for Exercise Performance in Eumenorrhoeic Women.” Sports Medicine, vol. 40, no. 3, 2010, pp. 207–27, https://doi.org/10.2165/11317090-000000000-00000.

5 Alvin, P. E., & Litt, I. F. (1982). Current status of the etiology and management of dysmenorrhea in adolescence. Pediatrics, 70(4), 516-525.

6 Ortiz, Mario I., et al. “Effect of a Physiotherapy Program in Women with Primary Dysmenorrhea.” European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, vol. 194, 2015, pp. 24–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.08.008.

7 Hackney, Anthony C. “Menstrual Cycle Hormonal Changes and Energy Substrate Metabolism in Exercising Women: A Perspective.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 18, no. 19, Sept. 2021, p. 10024, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910024.

8 Wikström-Frisén, Lisbeth, et al. “Effects on Power, Strength and Lean Body Mass of Menstrual/Oral Contraceptive Cycle Based Resistance Training.” The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, vol. 57, no. 1–2, 2017, https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.16.05848-5.

9 Minahan, Clare, et al. “The Influence of Estradiol on Muscle Damage and Leg Strength after Intense Eccentric Exercise.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 115, no. 7, 2015, pp. 1493–500, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-015-3133-9.

10 Rybaczyk, Leszek A., et al. “An Overlooked Connection: Serotonergic Mediation of Estrogen-Related Physiology and Pathology.” BMC Women’s Health, vol. 5, no. 1, 2005, p. 12, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-5-12.

11 Thiyagarajan, Dhanalakshmi K., et al. “Physiology, Menstrual Cycle.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2022, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500020/.